Monthly Archives: November 2018

Reflections on the genre of performance in music

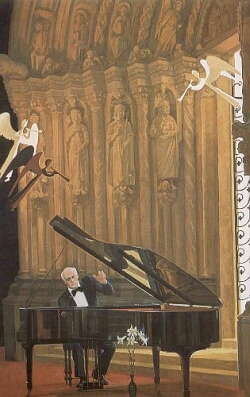

Any musical performance is a musical manifesto of the world, made in a shocking and entertaining way. But if, initially, the musical performance was aimed at changing society, at exposing the problems of society (just recall the Cage 4:33 experiment or some actions of the art movement “Fluxus”), then in its later interpretations the main goal becomes shocking . Today, performance has become an entertaining and completely harmless genre. Moreover, while in Russia in most of these musical experiments, they are still trying to express cosmic meanings (the same loud performances by the composer Oleg Karavaichuk), then in the West they have long ago switched to more “sparing” and at the same time accessible and understandable to the general public forms. Continue reading

Any musical performance is a musical manifesto of the world, made in a shocking and entertaining way. But if, initially, the musical performance was aimed at changing society, at exposing the problems of society (just recall the Cage 4:33 experiment or some actions of the art movement “Fluxus”), then in its later interpretations the main goal becomes shocking . Today, performance has become an entertaining and completely harmless genre. Moreover, while in Russia in most of these musical experiments, they are still trying to express cosmic meanings (the same loud performances by the composer Oleg Karavaichuk), then in the West they have long ago switched to more “sparing” and at the same time accessible and understandable to the general public forms. Continue reading

The story of the music

Music is the dance of sounds created by man. The language of music is sensual, uncontrollable, elusively flexible, unpredictable.

Music is the dance of sounds created by man. The language of music is sensual, uncontrollable, elusively flexible, unpredictable.

Music, like sculpture and painting, takes for itself material from the outside world; the case of the last two arts is a combination of colors and shapes; the cause of music is a combination of sounds. Music borrows sounds from the material world, but disposes of them freely. She picks them up and combines them at will; her work is continuous creativity. Continue reading

Sounds that do not exist

This is one of the most interesting effects inherent in some musical instruments and a chorus of people singing in about the same key — the formation of beats. When voices or instruments converge in unison, the beats slow down, and when they diverge, they accelerate.

This is one of the most interesting effects inherent in some musical instruments and a chorus of people singing in about the same key — the formation of beats. When voices or instruments converge in unison, the beats slow down, and when they diverge, they accelerate.

Perhaps this effect would remain in the sphere of interests of only musicians, if not the researcher Robert Monroe. He realized that despite the beating effect widely known in the scientific world, no one had studied their impact on the human condition when listening through stereo headphones. Monroe discovered that when listening to sounds of similar frequency through different channels (right and left), a person feels the so-called binaural beats, or binaural rhythms.

For example, when one ear hears a pure tone with a frequency of 330 vibrations per second, and the other a pure tone with a frequency of 335 vibrations per second, the hemispheres of the human brain begin to work together, and as a result he hears beats with a frequency of 335 – 330 = 5 vibrations per second, but this is not a real external sound, but a “phantom”. Continue reading